As some of you might remember, I keenly blogged some of the provisional OpenStax College (OSC) Educator survey results whilst I was in Houston for CNX2014 in April. Since then, there’s been some very minor changes made to these results and so I’m pleased to be able to correct these in a revised version of the post I originally published with some other additions (such as the sample overview table below). Most of the text is verbatim with % adjustments but look out for some bonus extra findings!

You can read more about the background to the work, and the methodology (e.g. what hypotheses we were looking at) in the original blog post. In the meantime, read on…

Sample

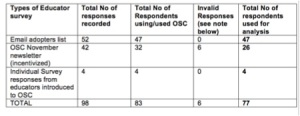

As noted in the previous blog post, and as in the table below, we recruited participants to the questionnaire via three channels (OSC email adopter list, introductions to educators from OSC and via the OSC newsletter). The latter (along with the student survey, which was also promoted via the OSC newsletter and subsequently on social media such as Facebook) was incentivised by a prize draw to win one of two $250 Amazon gift cards (the draw was overseen by OSC and only the emails and names of those who had consented to participate in the prize draw were passed under separate cover prior to data cleaning).

We received a total of 98 responses to the survey, with 83 respondents telling us they had or currently use OSC textbooks. Among these 83 respondents we identified a small number of invalid responses. These were largely duplicate responses which were identified by IP address and a very close review of respondents’ answers across surveys. I decided to remove the duplicate responses from the OSC newsletter survey respondents as it would have been the second instance where duplicate responders had answered the survey. Following the removal of these respondents and working with a slightly reduced sample size (N=77) to that originally reported, the results are as follows:

73.7% of respondents were male (n=56). The majority of respondents live in the United States (88.2%, n=67) and 11.8% of respondents living in either Australia, Singapore, Canada and Malaysia (n=9). Respondents’ ages were fairly even spread across the age groups (however, no respondents were under 25 or over 75 years old; reflecting perhaps the age at which people are qualified to enter the teaching profession and retire). All respondents had at least a Bachelor’s Degree with over half of respondents reporting that they had a PhD or Professional Doctorate (52.6%, n=40).

Over 75% of respondents conduct full-time face-to-face teaching (n=59) and nearly 95% of educators described themselves (in full or part) as a “Classroom Teacher” (94.8%, n=73). 13.0% of respondents are both Classroom Teachers and Department Chairs (n=10). 57.1% of educators spend at least part of their time working in the HE/University context (n=44) whilst just under a third of respondents teach in the K-12 sector (32.5%, n=25). Whilst no respondents reported that they carried out work-based training, just over 5% reported that they carried out some personal (one-to-one) tutoring in addition to teaching in other sectors (5.2%, n=4). Just under a quarter of respondents told us they worked in the Further Education/College sector (23.4%, n=18). Almost 70% of respondents who use or have used OSC textbooks have been teaching for more than 10 years (67.1%, n=51).

Over 80% of respondents teach Science (81.8%, n=63). Further analysis is needed to understand the relationship between those who teach, use OER and create resources in different subjects and this is currently future work. Over three quarters of respondents told us that they use Science related OER (76.6%, n=59) and over a third of respondents create OER in this subject area (33.8%, n=26). The need to examine these results in more detail is highlighted by the second most popular subject choice: Social Science. In this subject area a slightly higher number of educators use Social Science related OER (19.5%, n=15) than teach in that subject area (18.2%, n=14). As might perhaps be expected, however, there appears to be a relationship between the subjects taught by respondents and what OSC textbooks they are using: 62.3% of respondents told us they are currently using College Physics with their students (n=48) whilst 15.6% told us they were currently using Introduction to Sociology (n=12).

Use of the Internet and Open Educational Resources (OER)

Around 95% of respondents reported accessing the internet during the past three months at work and/or at home via broadband connection (96.1%, n=73 and 94.7%, n=72, respectively). 72.4% (n=55) of educator respondents who have, or currently use, OpenStax College textbooks accessed the Internet via a tablet computer or iPad and/or via a smartphone over this period (72.4%, n=55). Only 1.3% of respondents reported accessing the Internet via a dial-up connection (n=1).

We asked respondents to tell us what they had done over the past year (response choices ranged from use of particular software packages to online activities such as shopping online or sending an email). Although over 60% of respondents had contributed to a social network such as Facebook (63.2%, n=48) and/or shared an image online (e.g. via Pinterest or Instagram) (63.2%, n=48), a smaller number of respondents reported participation in other types of social media. Just under 15% of respondents had contributed to a Wiki (14.5%, n=11), whilst almost 30% of respondents had published a blog post (28.9%, n=22). Similarly 17.1% of respondents told us they had used microblogging platforms such as Twitter (n=13). It is perhaps worth noting that over half of those using microblogging platforms had also published a blog post in the past year (n=7). A higher percentage of respondents reported contributing to an Internet Forum in the last year (35.5%, n=27).

Although further analysis of the data is needed, it is of note that whilst 55.3% of people had downloaded a podcast, only 21.2% of respondents had recorded and uploaded their a podcast (n=42 and n=16 respectively). Elsewhere in the survey we asked respondents about the creation and adoption of OER. Whilst over 90% of respondents had adapted OER to fit their needs (90.9%, n=70) and just under half of respondents had created OER for study or teaching (48.1%, n=37) a much smaller number of respondents had created resources themselves and published them on an open license (14.3%, n=11) or added resources to a repository (31.2%, n=24). In a question further on in the survey we asked respondents what factors would make them more likely to select a particular resource when searching for OER. Nearly 60% of educators told us that the resource having an open license allowing adaptation would make them more likely to select a resource (59.2%, n=45) whilst just under 40% told us that the resource having a CC license would make them more likely to select a particular resource (39.5%, n=30).

The top three challenges faced when using OER were reported as as follows: Finding resources of sufficiently high quality (65.3%, n=49), knowing where to find resources (60.0%, n=45) and not having enough time to look for suitable resources (58.7%, n=44).

OER and Teaching

The top three types of OER used for teaching/training by respondents were reported as follows: open textbooks (98.7%, n=76), videos (79.2%, n=61) and images (72.7%, n=56). The former (and number one) response is perhaps no surprise considering the filtering of survey responses (e.g. 100% of respondents have or currently use OSC textbooks) although it is of note that one respondent did not associate OSC textbooks with the term “open textbook” (whether a mistake/oversight or for another reason, unfortunately we don’t know why this was the case. Similarly, in the newsletter version of the questionnaire for the OER behaviours question we introduced an additional option “I have used Open Educational Resources” and 96.2% of respondents to this version of the questionnaire told us they had used OER (whilst all had used or were using OSC textbooks) (n=25)).

The top three purposes for using OER in the context of teaching/training were reported as follows:

- As a supplement to one’s own existing lessons or coursework (96.1%, n=73);

- To get new ideas and inspiration (80.3%, n=61) and/or as “assets” (e.g. images) within a classroom lesson (80.3%, n=61);

- To prepare for my teaching/training (76.3%, n=58) and/or to broaden the range of resources available to my learners (76.3%, n=58).

Of note is that a third of educators reported using OER to interest hard-to-engage learners (34.2%, n=26) and a quarter reported that they use OER to make their teaching more culturally diverse (or responsive) (25.0%, n=19).

Almost 90% of respondents thought their students saved money by using OER (88.3%, n=68), whilst almost 60% thought their institution benefited financially by using OER (59.2%, n=45).

OpenStax College Textbooks

Nearly 40% of respondents first became aware of OSC textbooks via an internet or other search (38.2%, n=29) whilst 27.6% of respondents became aware of OSC via a colleague or other recommendation (n=21).

Although elsewhere in the survey just over a third of respondents told us that they use OER to interest hard-to-engage learners and a quarter of respondents use OER to make their teaching more diverse/responsive, in response to the question shown in the above presentation slide (which has been updated accordingly since the original post on these findings), when asked to tell us whether they agreed/disagreed with a variety of statements about OER/OSC textbooks, 67.1% (n=49) of respondents strongly agreed or agreed that OER allows them to better accommodate diverse learners’ needs. To better understand these responses, more work on the research findings is required.

The Impact of OpenStax College Textbooks on Teaching Practice

I will be working during summer 2014 on categorising responses to two questions asking respondents to tell us about any impact of using OSC on their own teaching practice and on their students.

In the instance of the former question, some educators reported no impact on their practice, or told us it was too early in their use of the textbooks to comment on possible impact/changes. However, there were a range of impacts on teaching practice noted by other respondents; a selection of these are given below. That OSC textbooks enable educators to be more responsive to their students’ needs was reflected in a number of educators’ responses to this question. One respondent noted:

“I am able to think a little more creatively of what new experiences I can design for my students using resources in the text or other online resources. I think the text is a great foundation, but I don’t feel constrained to shy away from employing other teaching tools for fear they might ask: “Well, if you were going to have us watch this video or do this online tutorial- why did we have to pay $250 for the textbook?””

Elsewhere others similarly commented:

“More satisfying to offer free materials and have the freedom to modify them as I wish, to make the product students receive more like how class operates.”

“I have become more intentional about tailoring my course to my students, having been at least somewhat released from the constraints imposed by the commercial publishing industry”

“Greatly increased my enjoyment in teaching physics as I can personalize lessons to match my own interests and our lab facilities…”

Other responses to this question include:

“I feel that I am now part of a larger body of teachers in the international context who are teaching the same topic with the same or modified text…”

“I appreciate the resources that OpenStax provides (e.g. PPT, quiz questions, videos) as well as the ease with which I can quickly find a full chapter written on a topic I am teaching or a very specific topic, along with media. I also really like to expose my students to other images and tables in addition to their textbooks’ images, and OpenStax allows me to do this without worrying about copyrights. I find myself comparing my lecture notes that I am about to present to my students with OpenStax books, and am gaining an interest in developing more and more OERs myself.”

“I am able to do many more in-class activities, hand-on engagement with the “concepts” of the course AND I can feel good about insisting on students reading and engaging with the text, when I know that cost is eliminated as a limiting factor for students.”

Looking for examples of impact on practice elsewhere in the survey, it is worth highlighting several several findings from a question where we asked respondents to tell us whether they were more or less likely to do a range of activities, following use of OSC textbooks. Over 90% of respondents told us they were more likely to make OSC textbooks the required text for students (92.0%, n=69). Nearly 80% of respondents told us that they were more likely to use other OER for teaching as a result of using OSC textbooks (79.5%, n=58) whilst 80.0% of educators who have used//are using OSC textbooks are more likely to discuss using OSC materials with their institution’s administrators (n=60). Over 40% of respondents also told us they were more likely to remix OSC textbooks using the Connexions platform (43.1%, n=31) following use of OSC materials.

Educators’ Perceptions of the Impact of OpenStax College Textbooks on Students

Regarding their perception of the impact of OSC textbooks on their students, educators again had a range of responses. Financial savings were frequently referred to, as where the accessibility/flexibility of materials. For example:

“It saves all 800 students per year about $120. One student told me that she had to work 15 hours for each book that she has to buy. That really put it in perspective.”

“Access. Access. Access. We are at a college that predominantly serves low income students. OpenStax provides students a great text at the best price (free) or for a nominal fee if one wants a printed edition. It has solved the problem of students not having or delaying getting the text due to financial concerns.”

“The resource gave them a sound understanding of the topic and they were able to do self-directed study from it. The result is that seniors have excelled in their exams.”

Whilst these (and other) comments are great examples of the types of impact OSC textbooks have had, it is useful to examine respondents’ comments for any evidence that it is “open” rather than “digital” which makes a difference. Whilst cost savings are one benefit highlighted by survey respondents, it is also of note that several educators referenced the way in which OSC textbooks gave students the opportunity for earlier and/or continued use of study materials. I have cited three such responses below. Further research into what kinds of (if any) impact results from earlier/continued access to resources in comparison with other materials is needed. For example, does earlier access to study materials (as students don’t have to save up or wait for funding) lead to better performance? Moreover, does continued access to learning resources (rather than, for example, an online textbook available for a set period of access) lead to better grades/more interest in one’s subject etc. both within the context of current and future studies?

“They have the book as a resource after leaving class. With another text they would most likely sell it back…”

“Increased reading of the textbook, and a portable textbook that can go with them for review. Unlike other e-textbooks, this one can stay with them.”

“They are able to access the textbook and start doing homework immediately rather than being delayed until weeks after the start of the course due to lack of finances.”

Leave A Comment